When the Jews of Prague picked up the community's official newspaper, The Jewish Bulletin

, on Friday the 13th of September

1940, they could not have missed the announcement printed in bold type on the righthand side of the front page. The New

Regulation for Jewish Renters in Prague

succinctly stated that the SS Central Office for Jewish Emigration had decreed: Jews

in Prague are no longer permitted to rent vacant residential properties.

From then on, Jews in the capital would only be

allowed to move into residences currently or previously occupied by other Jews.1 For more than year the Jewish Community's

Housing Department had already struggled to find accommodations in Prague for a growing number of Jews. Those efforts had

faced numerous challenges, including German officials' haphazard seizure of Jews' homes and the reluctance of many landlords

to take on non-Aryan

tenants. The New Regulation for Jewish Renters in Prague,

however, represented a particularly ominous

step in the persecution of the Bohemian and Moravian Jews. For the measure was just one of several critical decrees in autumn

1940 that redefined housing in the Protectorate and forced Jews into a ghetto without walls.

From the onset of the Munich Crisis through the summer of 1940, Jews from around Bohemia and Moravia had moved to Prague

in considerable numbers to flee rising antisemitism in their home towns and to seek avenues for emigration from their homeland.

First, in 1938 came the Jews of the Sudetenland. In the months that followed the March 1939 German occupation Jews from around

the Protectorate also relocated to the capital city in response to Nazi repression elsewhere in Bohemia and Moravia. Although

the SS Central Office for Jewish Emigration's original plan to concentrate all Protectorate Jews in Prague was suspended with

the outbreak of the war, the Jewish Community reported in September 1939 that the scale of individual migration of provincial

Jews continued to grow. 2 In response, the community established a special Housing Department

to find accommodation for

new arrivals to the city. 3 By late October 1939 the department reported the arrival of numerous Jews from the provinces,

for whom suitable rooms were found only with considerable effort.

4

The task was complicated by a concurrent increase in the number of native Prague Jews who needed housing. Some had apparently

cancelled their leases in expectation of emigration, only to find that they could not arrange the permissions and visas necessary

to leave the Protectorate. Overall, the community reported a great need for smaller residences, a sign of the growing impoverishment

of Jews who, fired from their jobs and with their assets frozen, could no longer afford their current rents.5 With the New

Year of 1940, another wave of applicants deluged the Housing Department. The community's weekly report noted: the circumstance,

that more and more Aryan landlords are no longer willing to have Jews as tenants, forces the interested parties to give up

independent searches for apartments

and turn to the community for help instead.6 Over the next several months, news of cancelled

leases and capricious, rapid evictions became a staple in the community's weekly reports to the SS Central Office. Whether

landlords evicted Jews because of antisemitism or a belief that they could find better paying, and lower risk, Aryan

tenants,

the development placed an even larger burden on the community. By the beginning of spring 1940 the Housing Department pleaded

in its report to the SS Central Office: The situation of the Prague housing market is become more and more critical by the

day and is now already assuming a catastrophic state.

7 Later that month the city of Prague exacerbated the predicament when

it suddenly cancelled the leases of all Jews in municipal apartment buildings.8 By the end of June 1940, the Housing Department

of the Prague Jewish Community reported that 11,648 Jews had sought its assistance.9

Only three days before the announcement of the New Regulation for Jewish Renters in Prague

, the SS Central Office ordered

the Jewish Community leadership to provide a full accounting of all residences inhabited by Jews in Prague.10 The timing

of the two measures was hardly coincidental: The German occupiers wanted a clear accounting of all residences where Jews lived

in order to be able to limit them to moves between them and to lay the groundwork for the seizure of the properties. Critically,

the SS Office demanded not a list of properties owned by Jews, but of all those where Jews resided, regardless of who had

legal title to the property. The plan to appropriate control over all such Jewish residences

became publicly clear on 7 October

1940, when the Reich Protector's Office announced that the SS Central Office must give approval before a landlord could rent

any residence previously occupied by a Jew. In other words, a property was to be considered a Jewish residence

if a Jew currently

lived within its walls, regardless of who owned it. A Czech newspaper explained to bewildered Aryan

landlords: The order speaks

of residences rented to Jews and does not thus distinguish between whether the landlord is a Jew or an Aryan. Only the race

of the renter who last lived in the residence is decisive.

11 The decree thus essentially racialized the bricks and mortar

that encased living spaces and summarily restricted the power of numerous non-Jews (both Czech and German) to dispose freely

of their own property.

Inadvertently, however, the Nazi racialization of residential space also handed Jewish tenants a means to defend themselves

against unscrupulous landlords. In a form of passive resistance, across the Protectorate Jewish community officials seized

upon the 7 October decree to protect their constituents. When Marie Bader's landlord in Prague tried to force her to move,

she reached out in desperation to a contact in the Jewish Community, who told her not to worry because she lived in a Jewish

apartment

that could be rerented only with the approval of the SS Central Office. Bader explained in a letter to her beloved

in Greece: Since yesterday I know for certain that I can keep my flat, indeed must keep it, and that the owner cannot demand

that I move out because she has absolutely no right to dispose of it.

12 Outside of Prague, local Jewish officials used the

same tactic to fend off aggressive landlords. In the Slaný district an elderly woman who faced eviction wrote the Jewish

community representative: In a hopeless state I turn again to you and ask for advice… I’m terrified… I’m abandoned.

13

The official responded: Be so good as to inform your landlady that, according to the order of the Reich Protector for Bohemia

and Moravia from 7 October 1940, it is necessary in regards to the disposal of apartments vacated by Jews to request the approval

of the Office for Jewish Emigration in Prague.

14 The Jewish Community in Holešov similarly explained to a Jewish representative

in nearby Bystřice pod Hoštejnem that, though Jews no longer had any tenants' rights, he should inform the landlord… that

he would gain no advantage from the eviction of this family because the home cannot…be rented again and so it would be more

advantageous to him if he left the family in the home.

15

The Jewish Community's efforts to protect Jews from eviction by private landlords could not, however, protect them from the

SS Central Office, which over the next two years used the property lists to carry out the mass concentration of Jews into

fewer and fewer apartments in specific districts of the capital city and in specific towns throughout the Protectorate. Autumn

1940, not coincidentally, also brought a radical restriction in the freedom of movement of the territory’s Jews. Three days

after the 7 October Reich Protector's decree, at the Germans' behest the Protectorate Interior Minister, Jaroslav Ježek,

issued a directive that made it illegal for Jews to change their place of residence without prior approval from the authorities.

The independent relocation of Jews from the provinces to Prague had officially come to an end. Thereafter the authorities

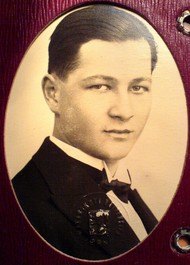

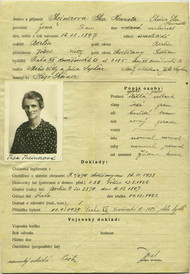

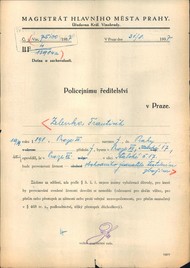

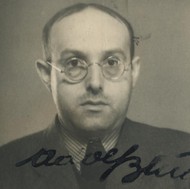

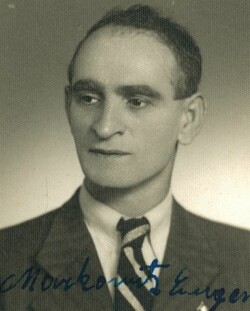

punished Jews who moved on their own initiative, including, for example, Evžen Markovits, whom the police arrested in August

1941 for relocating within the city of Prague without prior authorization. For Markovits that was just one of several arrests

he endured, which ultimately contributed to his direct transfer in June 1942 from the jail of the Prague police to the SS

collection site in the city's Holešovice district and thereafter on to the Theresienstadt Ghetto and, ultimately, his murder

in German-occupied Belarus.

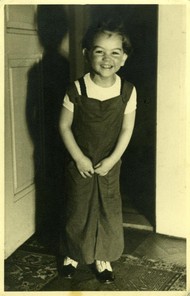

Evžen Markovits in 1940 (Photo: Národní archiv ČR, fond Policejní ředitelství)