By the end of the 1930s, Germany was experiencing the stabilisation of the regime, economic consolidation and intensive preparation for an aggressive war. Fear of damage to Germany's economy and to its international political position.

Germany's first territorial gain was Austria, which was annexed in the Anschluss on the 12th of March 1938. The occupation of Austria immediately provoked a wave of anti-Jewish measures and incidents, the intensity of which grew out of a long tradition of Jewish anti-Semitism. Jews were attacked and harassed in the streets, had their property stolen by Austrian Nazis, were moved out of their flats and in some cases were even driven over the border. The process of excluding Jews from society, which in Germany had been going on for five years, took only a few months in Austria. On the 20th of August 1938, Adolf Eichmann (link in Czech), an SS specialist

on the Jewish question, set up the Centre for Jewish Emigration in Vienna. In exchange for the opportunity to emigrate, it required Austrian Jews to surrender almost all their movable and immovable property to it. Through a combination of administrative perfectionism and daily terror, almost two thirds of Austria's Jewish population - 130 000 people - had been driven out by the end of 1940.

The increasing radicalisation of anti-Semitism in Germany brought on a further wave of anti-Jewish incidents, culminating on the 9th of November 1938 with the Reichskristallnacht, a nationwide pogrom organised by the Nazi regime, during which most of the country's synagogues were burnt down and the remaining Jewish shops were vandalised. Approximately 100 Jews were killed, and around 30 000 more were taken to concentration camps. The Nazis accused the Jewish population of provoking the pogrom, and ordered the Jews to pay a billion Reichsmark as punishment... The Nazi regime also confiscated all the insurance payments that belonged to the Jews whose property had been damaged, while at the same time ordering them to renew the appearance of the street

at their own cost. The Kristallnacht was used to speed up the process of Aryanising what was left of Jewish property.

Pedestrians passing the window of a Jewish shop in Berlin, broken during Kristallnacht. (Photo: National Archives, courtesy of USHMM Photo Archives)

1938 was a watershed year for Jews in Germany. As it prepared for military conflict and territorial expansion, the regime stepped up the pressure for the complete exclusion of Jews from society. The aim was for Jews to become an impoverished caste on the fringes of society, with no prospects of a normal existence. In pauperising the Jewish population and removing their means of supporting themselves, the Nazis themselves created a Jewish problem

, the logical solution

to which was the later deportations to ghettos and concentration camps. The process of Aryanisation, now proceeding at full tilt, was not driven only by the greed of those implementing it, but primarily by the Nazis' anti-Semitic ideas regarding the need for society to be totally purged of Jews.

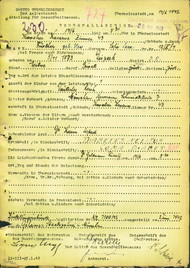

Jews were banned from working in many areas, above all in small-scale commerce. In July 1938, all Jewish doctors had their professional qualifications revoked, followed by all Jewish lawyers in September. In April a decree was introduced requiring the declaration of all Jewish property exceeding 5 000 Reichsmark in value. This resulted in property worth over billion Reichsmark being ascertained. The third decree accompanying the Nuremberg laws (link in Czech) defined the concept of a Jewish enterprise

. For a company, it was enough to have a single Jew on the supervisory board, or a quarter of the capital in Jewish ownership. Later, Jewish enterprises

were also defined as those under the dominant influence of Jews

. These definitions provided a tool for the Aryanisers, who saw an opportunity to feed off the demolition of Jewish life in Germany and Austria.

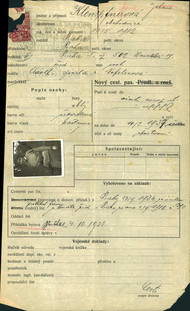

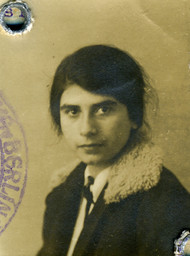

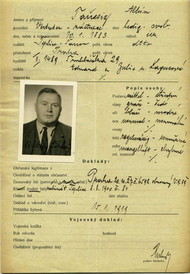

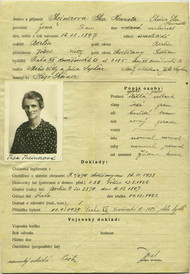

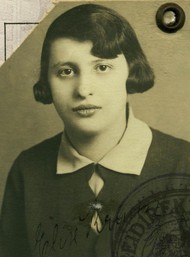

Measures were also taken to ensure that Jews were labelled. In July 1938, a decree was introduced requiring Jews to have special identity cards, and from October 1938 on, the passports of German and Austrian Jews had to be stamped with a J

(for Jude

, Yew

). From the 1st of January 1939 onwards, all Jews were compelled to take the obligatory additional given name of Israel (for men) and Sara (for women), and newly-born Jewish children were not allowed to be given German

names. A special list of permitted names, which were clearly Jewish at first sight, was drawn up for them.

These events meant the disintegration of the gradual, organised and well-prepared emigration process that the leaders of the Jewish organisations had pushed for until 1933. After the Austrian Anschluss, there were no longer any illusions regarding the future existence of Jews in Germany, and Jews tried to leave the Nazi sphere of influence at any price. As the tide of refugees grew, however, the opportunities to escape declined, with fewer and fewer countries willing to accept Jewish emigrants from Germany and Austria. At the suggestion of US President Roosevelt, representatives of 32 countries met in Evian, France in July 1938 to discuss the possibilities of helping Jewish refugees. The conference ended in huge disappointment: with the exception of the tiny Dominican Republic, all the countries involved refused to increase their opportunities for immigration.