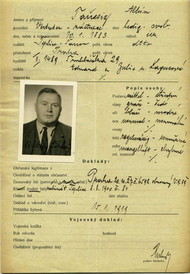

After the deportation of the majority of the Roma population, an unspecified number of Roma remained in the Protectorate. A group of about two hundred of them, who were released during the assembly of transports with the permission of the criminal police, was probably to undergo forced sterilization in the future.1

Those who were not identified as gypsies and gypsy half-breeds

in the census of gypsies

had the best chance of survival,

since they did not even get into the process of final solution

. This is how for example Eduard Holomek managed to survive.

In 1941, with the help of a friend, he got on the list of young men who were sent to the Reich. During the war, he worked

in an ammunition factory near Vienna.2

Other Roma hid (eg with relatives, friends or in the woods), some fled to Slovakia.3 But a succesful escape from a camp did

not mean safety yet. Larger groups (eg families) moved more slowly, were more conspicuous and had difficulties finding shelter

and food. An individual may have had a better chance of escaping, but on the other hand he often had to decide to leave his

loved ones behind without knowing if they would ever meet again. The refugees had to hide not only from the security authorities,

but also from the majority population. Although there were people who tried to help in various ways, such as providing temporary

or permanent shelter, food, etc., not everyone was willing to take risks and help, even less to gypsies

, stigmatized by prejudice

and contempted. The genocidal measures of the authorities were based on the racist attitudes of the society of that time.

People commonly agreed with the gradual radicalization aimed at suppressing the rights of various groups of the population

and ultimately leading to their extermination. Moreover, anti-Gypsyism, similar to anti-Semitism, was constantly fueled by

propaganda in the press and radio during the Nazi regime.

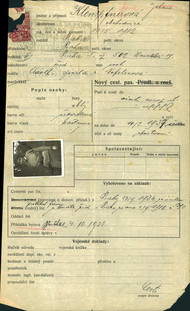

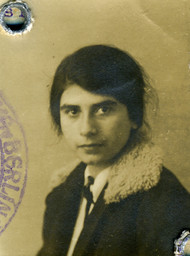

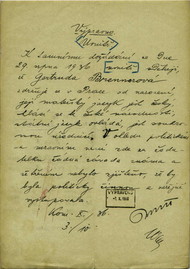

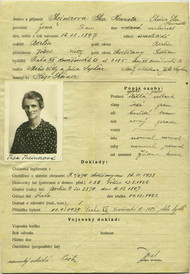

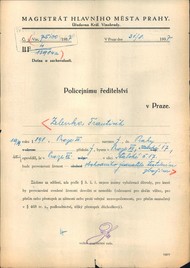

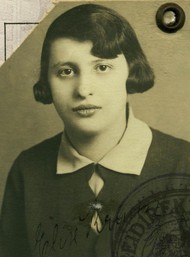

Zilli Schmidt (born Reichmann in 1924) a German Sintezza, who fled the gypsy camp

in Lety u Písku in November 1942, had

a painful fate. After a few days on the run in the Protectorate, she was arrested again and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau

in March 1943. Later that year, she also met her three-year-old daughter, parents and other relatives there, who in the meantime

had also been imprisoned at the gypsy camp

in Lety u Písku, subsequently also in Hodonín u Kunštátu before being deported

to Auschwitz-Birkenau. While Zilli was taken to the Ravensbrück concentration camp on August 2, 1944, the rest of the family

was sent to the gas chamber that day. She later escaped from a branch camp of Ravensbrück and hid in Berlin, where she was

liberated. After the war, she settled in Germany, where she still lives and testifies to her persecution.4

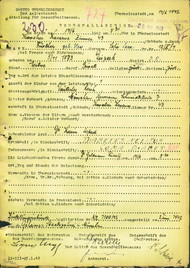

Some individuals also took an active part in the anti-Nazi resistance. E.g. Josef Serinek (1900–1974), who in the autumn

of 1942 successfully fled the „gypsy camp“ Lety u Písku, went on to form a guerrilla unit named Čapajev

, often though

called Černý

(Black

) and became famous in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands.5 Another fighter was Antonín Murka (1923–1989),

who joined the anti-Nazi resistance in his native region of Valašsko (Wallachia) in Moravia after escaping from the gypsy

camp

Hodonín u Kunštátu.6

Next chapter: Conclusion