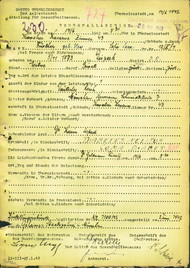

On December 16, 1942, the head of the German police and SS, Himmler issued the so-called Auschwitz-Erlass (Auschwitz decree),

which ordered imprisonment for all Gypsies, Gypsy half-breeds and non-German members of Roma groups of Balkan

origin in the

Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination and concentration camp. This deportation order applied to the territory of the Great German

Reich, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. Himmler's decree was subsequently

supplemented by the Reich Security Office on January 29, 1943 with an implementing directive and on January 30, 1943 containing

instructions for the confiscaton of the property of gypsies

as enemies of the Reich

.1 At the same time, this decree marked

the end of all other plans for the future of Roma and Sinti that the Nazis had previously discussed.

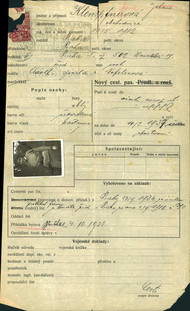

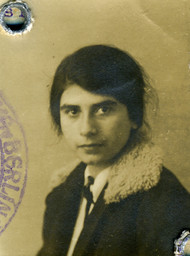

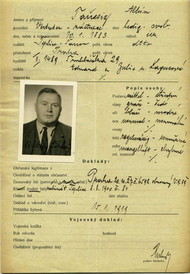

The preparations for the deportations from the Protectorate were kept secret. The compilation of the transports was ordered

by the German criminal police, and the execution itself was entrusted to the protectorate's criminal police and gendarmerie.

Based on their racial investigations

, the criminal police decided who they considered a racial gypsy

or half-breed

and because

of this categorization would be deported.2

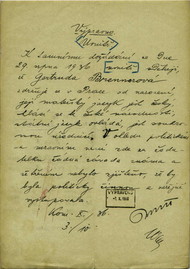

Only those with good connections to that part of society that had contacts with the occupiers which could be made use of,

had a certain chance to be excluded from the transports. One such case was the family of the famous Roma musician Jožka Kubík

(1907–1978) from the village of Hrubá Vrbka.3 There was also some hope for those with a lighter skin color, bribing police

men sometimes worked, too. At the end of April 1943, the protectorate police in Moravia was reprimanded by the German criminal

police for the high number of exemptions

it had granted. Most of these exemptions granted were revoked by the Criminal Central

Office and the people concerned were deported anyway.4

Originally, the Protectorate Criminal Police and the non-uniformed Protectorate Police had planned to deport the prisoners

of the gypsy camps

in Lety u Písku and Hodonín u Kunštátu first. However, these plans were changed due to the typhus

epidemic that broke out in both camps. Officials feared that the epidemic could spread into the Auschwitz concentration camp,

and so those men, women and children labelled as racial gypsies and hald-breeds

but so far living outside of the camps were

deported first.

In larger cities connected to the railway, they were gathered for several days at so-called collection points – in occupied gyms, inns and other facilities, where they spent several days before the transport. All their money and property were taken from them, in many cases stolen, sold at public auctions or confiscated by the Reich.5

After the transport was assembled, the journey by rail in freight wagons without food and drink to the gates of Auschwitz-Birkenau

concentration camp followed. There, Roma and Sinti from the Reich and other European countries directly controlled by the

Nazis were imprisoned in a special section B-II-e called the Gypsy Family Camp

, where over 22,000 Roma and Sinti men, women

and children were gradually interned. Most of them died there.6

The first mass transport of protectorate Roma, numbering 1,038 people, left Brno on March 6, 1943.7 During 1943, further

transports followed from various parts of Bohemia and Moravia, as well as from both gypsy camps

, arriving in Auschwitz on

March 10 (the transport sent from Prague numbered 650 people), March 19 (1,048 people from Olomouc). On May 7, the transport

of prisoners left the camp in Lety u Písku (863 people), and on August 22, the transport from the camp in Hodonín u Kunštátu

(768 people) followed. The last transports left on October 19 (from Prague and Brno, 92 people) and on January 28, 1944 (from

Prague and Brno, 37 people). In total, the protectorate authorities gradually deported about 4,500 protectorate Roma and Sinti

to Auschwitz by mass transports of gypsies

. More than a hundred other people were deported individually.8

.s.2.jpg)

Ill. 6: The Abolition of „Gypsyness“. In: Polední list. [Afternoon daily.] Prague, March 8, 1943, No. 17, p. 2.

Ill. 7: Roma from the village of Bohusoudov (Jihlava district) gathered for their deportation to the Auschwitz II.-Birkenau concentration camp, 1943.

Next chapter: Escape, survival and resistance