As the largest Nazi concentration and extermination camp, the concentration camp complex near the Polish city of Oświęcim

(Auschwitz) has become a symbol of the suffering and death of more than a million men, women and children from all over Europe.

The extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where predominantly Jews, Roma and Sinti were murdered, played a crucial role

in the systematic mass murders committed by the Nazis. At Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazis imprisoned various groups of people

in different sections of the camp. In section B-II-e, there was a gypsy family camp

from spring 1943 to summer 1944, in which

about 23,000 European Roma and Sinti and others, categorized by the Nazis as racial gypsies and gypsy half-breeds

, were imprisoned.1

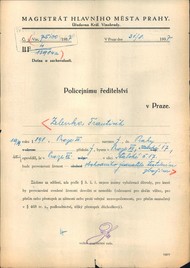

The line of action the German Nazis chose against the Roma and Sinti was prepared and defined in the German Reich, based

on Nazi racial science

and put into practice through various political measurements, culminating in mass murder in concentration

and extermination camps. The decree on the battle against the gypsy plague

, issued by the commander of the SS and police,

Heinrich Himmler on 8 December 1938, regulated the solution to the gypsy question

in the Reich on a racial basis. From May

1940 on, the first deportations of German Roma and Sinti from the Reich into the territory of occupied Poland took place,

where the Nazis imprisoned them in various camps and ghettos (for example in Łódź). Alongside the preparation and implementation

of the final solution to the Jewish question

, conditions were gradually created for the last stage of the final solution to

the gypsy question

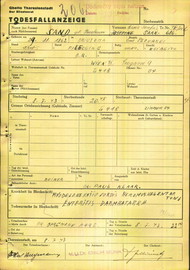

. The final decision on the fate of the Roma and Sinti not only in Germany, but in the whole of Nazi-controlled

Europe was published on December 16, 1942, when Himmler issued the so-called Auschwitz decree (Auschwitz-Erlass). This decree

and its implementing directives issued by the Reich Security Head Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt) on January 29, 1943,

ordered the deportation of gypsy half-breeds, gypsies-Roma and non-German members of gypsy tribes of Balkan origin

to the

Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp on former Polish territory annexed to the Reich.

An extended version of the text, including all sources, is available here.

Next chapter: Establishment and spacial organization of the camp