When the Nazis occupied what had been left of the territory of the former Czechoslovakian state and established their occupation

regime, they brought with them their racial ideology and thus the definition of foreign races

(artfremde Rassen

) as which

they considered Jews, Gypsies

and Negroes

.1 As Jews

2, they didn’t only consider those who also identified themselves

as such, but also people, who, for example, came from families who had converted to Christianity several generations ago.

They codified their definition of who was to be considered jewish

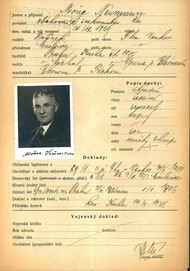

in the so-called Nuremberg Laws. The Nazis created a list

of their future victims in a long and complicated process. They used official documents, documents of Jewish communities,

and, in Germany, the census in order to compile a registry of those they considered to be jewish

solely for the purpose of

their persecution.3 Concerning those they considered gypsies

, they had to adapt their methods. The Nazi definition of gypsies

was

based primarily on the pseudo-scientific research of Dr. Robert Ritter, who since 1936 headed the so-called „Research Institute

for Racial Hygiene“ (Rassenhygienische Forschungstelle) at the Reich Health Office. This research institute used genealogical

research in combination with police registers and pseudo-scientific anthropometric criteria to determine who counted as a

racial gypsy

or gypsy half-breed

. This process began later than the creation of the list of Jews in the Reich and took place

mostly during the Second World War. After the establishment of the Protectorate, the Nazis quickly gained documents, which

enabled them to also determine in the Czech lands who was a Jew

according to the definition of the Nuremberg Laws. However,

they did not have similar documents regarding the gypsies

.

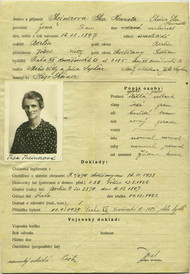

There was though a police register of Gypsies

, which the Czechoslovak police ran since 1925 and which was regulated by law

No. 117/1927 Sb. on wandering gypsies

. This law defined gypsies

based on lifestyle. Paragraph 1 of that law was worded as

follows: According to this law, wandering gypsies are considered to be gypsies wandering from place to place and other workshy

wanderers who live in the gypsy way of life, even if they have a permanent residence for part of the year, especially the

winter.

4

The vague definition of wandering gypsies

in this law reflects the general understanding of the term gypsy

in the Czech

society of that time. Gypsies

were considered on the one hand Roma and Sinti as an ethnic group (then called Gypsies

, in

Czech written uppercase), and, on the other, everyone who resembled the imagination of this group based on prejudices and

stereotypes (gypsies

, in Czech written , eg. vagrants, wandering grinders, umbrella repairers, wandering merchants, small

carousel operators). The Dictionary of the Czech Language from 1937 states that a gypsy

is a member of the wandering nation

of Gypsies

, but also a rogue, liar, impostor

in general.5

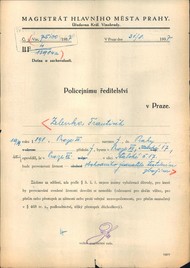

Before the Nazis used the beforementioned police register for their own purposes, various other measures from the Reich were

adopted in the Protectorate.

Next chapter: The occupation and implementation of German laws and regulations