Ela (left) with her sister Ilona and nurse Marie, 1934

I grew up in Lom u Mostu, where there was a very small Jewish community. They were mostly my relatives, my father's cousins and sisters, living in mixed marriages. My mother was from Moravia - they sent her to the Sudetenland to learn German. She met my father there and got married before she was even eighteen, so she didn't learn German very well.

Kristallnacht

I think it was the worst day of my life. Our father was no longer with us. As soon as the Germans entered the Sudetenland the Gestapo summoned him, because he was first on the list of the Reich's enemies. That was because he'd announced he would give ten thousand crowns to anyone who killed Hitler. After that we didn't see him any more, and we never even found out what happened to him.

Ela's childhood house in Lom u Mostu

On November 9th 1938 a friend of our father's came to us in the early evening and told us that a huge demonstration against us was being prepared in Dolní Lom, that my mother should close the shop that we had between Dolní and Horní Lom, and that we should prepare to be attacked. My mother still didn't believe it; she thought the Germans would sort it out between themselves. I can still hear today the sound of the drums, the Hitlerjugend on the march, drumming from Dolní Lom up to our house. When they came close to the house and shouted Juden raus, Juden nach Palestina, my mother pulled us out of bed. My aunty was sleeping there with us, and my mother said to her: Come on, Greta, we have to hide. She stuffed all her clothes into her nightshirt and we ran up to the attic. But my sister suddenly disappeared, she locked herself in the bathroom. Our chauffeur already knew that something was up. We had a pond in the garden, with carp in it for Christmas. He fished them all out and put them in the bathtub. Before we could get my sister out of the bathtub, people had broken all the windows and some had started to get into the house. They wanted to open the safe, and they took out what they could. We had a big porcelain collection, some of it they broke, some they left. We were in the attic, it was terribly cold and we only had our pyjamas on. A lady was living with us with her son, and I was friends with him. My mother begged her to at least let us, the two children, into her bed or to hide us in some other way. But they'd just released her husband, a communist, from prison, it was his first day at home, and she was afraid. She was afraid that they might find us with them. It went on all night. That was the longest night of our lives.

In the morning the water kept running, and my mother said: They want to flood us out. Then we heard them leaving, dragging the things from the house with them. Gradually we went downstairs to have a look. The first thing I saw was the bath full of red bloody water, with the carp swimming in it. It was bloody because they'd washed their hands in it after they broke the windows.

Expulsion

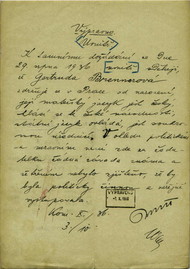

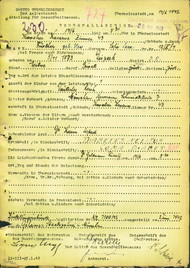

The next day, early in the morning, the Gestapo were standing at the door telling us that we had to have everything painted. The whole downstairs of the house was covered in graffiti, at the entrance to the shop was a gallows and above that was Saujuden and nach Palestina and so on. My mother was told that we were not allowed to photograph it, and that if it wasn't painted over, they would arrest her. They also called her in front of the Gestapo and told her to bring all her bank deposit books, all the documents from the shop and all her property. They held her at the Gestapo in Litvínov, and told her that we had twenty-four hours to leave Lom and our house. They said that until six o' clock the border between the Czech lands and the Sudetenland was open, and that if we didn't cross it before then, we'd go to Dachau. Of course, my mother had no idea what was going on now. To her, Dachau was a little town in Germany. But our chauffeur saw everything differently from my mother, he took our car and hid it, and so we had nothing to leave in. My uncle had a motorbike with one of those sidecars, into which they put my sister and me, and my mother sat behind him with nothing but her handbag. I think she was given three marks per person and a passport.

When we arrived at the border - Lovosice and Postoloprty - it was ten past six. It was autumn, nearly winter weather, it was raining and snow was falling, it was terribly cold. I started crying and begged my mother - come on, let's go home. Either the German soldier understood me, or he understood the situation, and said: Quick, quick. The Czech border guards stood there and said nothing. On the German side we could see a building with people lying on the floor, waiting to go to Dachau.

And so we crossed the border and arrived in Louny. My father's cousin had a chocolate factory there. We thought we might be able to stay the night there before we went to Prague. But the shop was full of people. They were sleeping all over the floor, because the Most and Teplice regions were very Jewish and everyone was trying to escape. So we slept in a hotel in Louny, and after that we went to Prague. That was November 10th.

In Louny we also heard that they'd set fire to the synagogue in Most and Teplice, that it was burning. We weren't devout Jews, but we did go once or twice a year to the synagogue in Most. Of course, I had no idea why all this was happening. All my mother told me was: Children, they've taken everything from us, we don't have anything any more, and that it was all because of the Grünspan-Affäre. All those years, my mother had no idea who Grünspan was or what affair it was, because all she knew about was the Dreyfus affair. She'd never heard of the Grünspan affair. I'll tell you when I found out who Grünspan was, you'll laugh. We were watching the History Channel in America because Brundibár was on, and they explained who Grünspan was and showed a photograph of him, and how he had killed von Rath in France, and that all the Jews under German occupation, including the Sudetenland, were made to pay for it. All that I knew back then was that my whole world had changed. Although I was only eight, I think I was grown up.

Later I would often dream about the synagogues burning on Kristallnacht, that to me was a terrible thing, why did they choose buildings in which people prayed. They just wanted to destroy everything that was reminiscent of the Jews. As a child I couldn't understand that, because I hadn't grown up in a devout family.

After the eviction

My uncle in Prague asked for a larger flat, because as a bachelor he only had a small flat. Before it came through, though, I was already living at my grandmother's in Brno. Brno was very German, and the environment in my grandmother's house was very typical, almost Jewish. There were some students lodging at my aunt's, and they wanted to emigrate to Palestine. I went to school there, and I remember how one day they took us from school to the station, because it was just round the corner, to act as a welcoming crowd for Hitler. They told us we didn't need to heil, we just had to stand there and welcome him. I couldn't even look at him. I'll tell you why. My father used to listen to his speeches on the radio. The whole radio shook when he roared Juden raus, and so we always put our hands over our ears. That's stayed with me ever since.