Most of those imprisoned in the gypsy camp

in Auschwitz-Birkenau died there as a result of hunger, disease and epidemics.

Those who were young, healthy, and fit for work and therefore deported further to other concentration camps, internment and

labor facilities had a certain chance of rescue, even though they were exposed to devastating work, inhuman living conditions,

forced sterilization or death marches in the last weeks of the war.

Of all Czech and Moravian Roma and Sinti imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau and other concentration camps, only about 600 men

and women returned to post-war Czechoslovakia. Persistent humiliation, extreme physical and mental violence, as well as persistent

anxiety, had a lasting impact on the physical and mental condition of the survivors and caused them trauma that haunted them

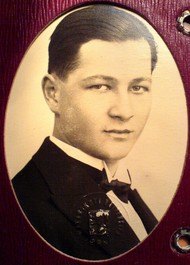

for the rest of their lives. Leon Růžička (born 1924 in Litoměřice, prisoners number Z-1931), who survived Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Mittelbau-Dora

and Bergen-Belsen, recalled: After the liberation of the camp, I returned home. There, I searched in vain for my family members.

I was the only one left, alone. How terrible! I cried with hatred for war. I hated it so much. All 27 members of our family,

including 13 children and our good mother, all were victims of the war, either perished in the gas chambers or by inhuman

abuse. I myself was ill and it took me several months to recover. But I never recovered completely.

1

The survivors usually tried to return to their hometowns or to the places from which they were deported, since they hoped to meet their relatives there. However, these returns were not easy for many of them. Usually, they couldn't find their homes and former residences, because Roma settlements or settlements on the outskirts of municipalities were often demolished by the relevant authorities after the deportation of their inhabitants, their belongs sold at public auctions, or their houses were allocated to other residents. The survivors, impoverished due to their persecution and deportation, thus had to cope not only with their poor health and the loss of their relatives, but also with the deterioration of their social status.

Among the survivors, particularly the survivors of the Czech and Moravian Roma and Sinti, the memory of their tragic fate during the Second World War was, of course, alive and present. However, in fear that these horrors might repeat themselves, because of their stigmatization in the eyes of the public, and for persistent prejudices, some survivors refused to talk about the traumas they had experienced, or preferred not to speak about their Roma identity at all.2

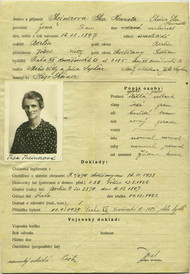

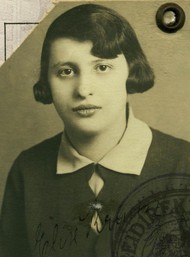

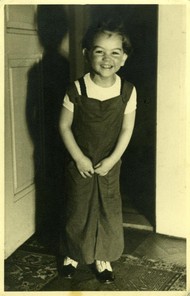

Aloisie Blumaierová (born 1926 in Bořitov, Blansko district), who was imprisoned in the Auschwitz, Ravensbrūck concentration

camps and a branch of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Kraslice and later survived a death march, recalled: I returned

home, but with poor health. I had rheumatism in my spine and mentally I was completely torn. I couldn't have children for

a long time, and when they were finally born to me, I was still worried about them not having to go through something like

me. Those were the consequences of my forced internment in the concentration camps.

3

Despite its seriousness, the topic of the Roma Holocaust, was not reflected by societies` majorities, both in Eastern and

Western Europe, after 1945. The struggle of Roma and Sinti for recognition as victims of racial persecution during Nazism

and for their inclusion into the collective memory lasted for several decades. It was not until the 1960s that the international

Roma movement became active, one of its first demands being the recognition of the racial persecution of the Roma. Also, the

first acts of remembrance to commemorate the victims of the genocide of Czech and Moravian Roma and Sinti took place at the

end of the sixties, respectively at the beginning of the seventies, thanks to the instigation of survivors and members of

the first Czech Roma organization, Svaz Cikánů-Romů (Union of Gypsies-Roma) (1969–1973).4 Despite these isolated efforts,

however, public commemoration of the genocide of the Roma population in Czechoslovakia was minimal, there was only limited

historical research and little recording of survivors' statements. The historical memory of the Roma as a group on the margins

of society has thus not become part of the consciousness in greater parts of society. It was only after 1989 that public remembrance,

education and research on the topic developed. Commemorative events are regularly held not only at the places of the protectorate

gypsy camps

. One of the oldest act of remembrance commemorates the mass deportations of Roma and Sinti to Auschwitz, and take

place every year in Brno (in March), Lety u Písku (in May) and Hodonín u Kunštátu (in August). Since 2002, Roma victims

of Nazism have also been included into the agenda of the International Holocaust Day of 27 January, commemorating the liberation

of the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1945.5

The tragic events of the Nazi genocide of Roma and Sinti are gradually gaining ground in pan-European and world history. The

former Auschwitz concentration camp plays a crucial role in the context of remembrance and educational activities. In 2001,

the permanent exhibition of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Auschwitz, in cooperation with the Central Council of German

Sinti and Roma, was expanded to include a section on the persecution of European Roma and Sinti.6 In 2002, the tragic fate

of the Roma and Sinti became part of the new permanent exhibition of the Auschwitz Museum dedicated to imprisoned people from

the Czech lands. Among others, the Terezín Memorial and the Brno Museum of Romani Culture contributed to this exhibition. The former gypsy

camp

at Auschwitz-Birkenau becomes a place of remembrance each year on August 2, bringing together representatives of Roma

organizations and governments, diplomats, survivors and witnesses not only from Europe. This date, commemorating the liquidation

of the gypsy camp

at Auschwitz-Birkenau and the mass murder of men, women and children imprisoned there in 1944, was declared

the International Roma Holocaust Day.7

Monument on the site of the former gypsy camp

in KT Auschwitz-Birkenau during the memorial act on August 2, 2018. (picture:

Michal Schuster).

Conclusion

The gypsy family Camp

, in section B-II-e of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination Camp, formed an integral

part of the Nazi genocide of Roma and Sinti and others categorized as racial gypsies and gypsy half-breeds

. During its existence

from February 1943 to August 1944, about 23,000 men, women, and children from various parts of Europe passed through the camp.

Among them were about 5,500 Roma and Sinti from Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, who were deported to Auschwitz during the years

1943 and 1944 from the Protectorate and the former Czechoslovakian territories annexed to the Reich. The catastrophic conditions

in the camp, concerning nutrition, accommodation and hygiene were the major cause of mass mortality in the gypsy camp

with

only very limited health care. A total of about 19,300 people died in the camp, including about those 4,300 men, women and

children murdered in the gas chambers during the liquidation of the camp on the night of August 2-3, 1944. The date of August

2 became a symbol of the final solution to the gypsy question

and institutionalized as International Roma Holocaust Day. The

victims are commemorated not only on the site of the former Auschwitz concentration camp, but also in several places in the

Czech Republic.