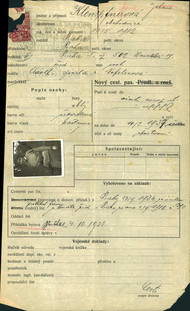

Deportations and the number of people imprisoned

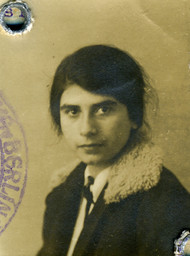

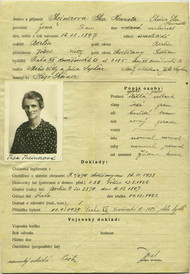

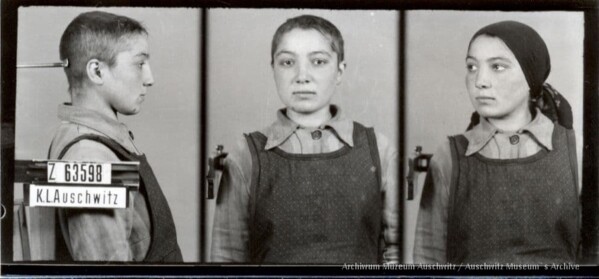

Unknown woman with prison number Z-63598, one of the few surviving photographs from the "gypsy camp" in concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. (picture: Archive of the State museum at Auschwitz-Birkenau)

The gypsy camp

in section B-II-e was in operation from the end of February 1943 to the beginning of August 1944, and throughout

this time, deportations of more or less numerous groups and individuals from the Reich and occupied European countries came

in. Initially, future prisoners were brought in small groups, the first of them arrived on February 26, 1943. During the first

three weeks, thousands of Roma and Sinti were deported to the newly opened and as yet unfinished camp. By the end of March

1943, there were more than 12,000 men, women, and children in the gypsy camp

, including those born in the camp, registered

as prisoners here. The largest influx of prisoners occurred in the first and then in the next two months after the establishment

of the camp. Then the deportations were substantially reduced, with the exception of August 1943, when 768 people from the

Protectorate were deported in a single transport, and gradually renewed from December 1943. Of the approximately 20,900 victims

registered in the gypsy camp

, 18,700 were deported in 1943, and 2 200 during the following year. In total, about 23,000 men,

women and children passed through the camp during the less than 17 months of its existence. This plain number hides the tragic

fates of individuals, most of whom have died.1

In total about 10,200 German Roma and Sinti were deported to the gypsy camp

at Auschwitz-Birkenau, mainly during 1943 from

various local concentration camps where they had previously been assembled.2 2,600 to 2,900 Austrian Roma and Sinti were brought

to the camp in several mass transports from March to May 1943.3 More than 3,000 Polish Roma from the General Government came

to the camp mainly from gypsy camps

that had been set up to prepare the deportations.4 In spring 1944 Roma and Sinti were

deported from the German-occupied Netherlands to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A transport with 245 Dutch, Belgian and German Roma and

Sinti arrived from the Westerbork concentration camp on May 21, 1944. Transports from Belgium took place in November 1943

and January 1944. On 17 January 1944, 351 people arrived in the camp, including individuals not only Belgium but also from

France, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain and Norway.5 In the spring of 1944, deportations took place also from the territory

of the Soviet Union, by then occupied by the Nazis. Roma from Brest, Lithuania, which belonged to the Belarusian General Commissariat,

and from Lithuania were deported to the "gypsy camp" in Auschwitz-Birkenau.6

Prisoners from Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia

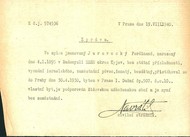

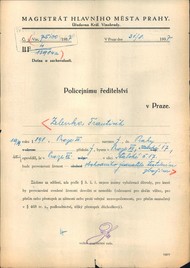

The Deportations of Roma and Sinti from the Protectorate, based on Himmler's so-called Auschwitz-decree, took place during 1943 and 1944. People were deported either individually, in larger or smaller groups or more often by means of mass deportations, which usually consisted of tens and hundreds of men, women and children previously assembled at so-called collection points (sport clubs, inns and other buildings). Transports took place by rail, the people were crammed into freight cars with tightly closed doors and windows and had no access to food, drink and toilets during their many-hour journey (for example, the journey from Prague to Auschwitz). The trains started from Prague and went via Pardubice, Brno, Přerov and Moravian Ostrava to Auschwitz. On the territory of the Protectorate, the deportation trains were operated by the Czech-Moravian Railways and beyond the borders of the Protectorate, by the German Reich Railway (Deutsche Reichsbahn). Accordingly, the non-uniformed police of the Protectorate and the gendarmerie escorted the trains to Moravian Ostrava, where the German criminal police took over at the border.7

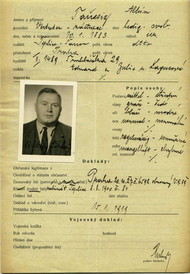

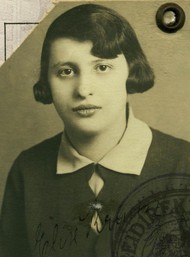

Iren Herák (born 1912 in Ludkovice, prisoners number Z-4446), imprisoned in the concentration camps Auschwitz-Birkenau, Buchenwald and Mittelbau

I-Dora, recalled: We left from Uherský Brod in trains with freight cars. The freight cars were crammed with people, so that we could

hardly move. There was no toilet, just a tin pot, I remember this like it happened today… We didn't know where we were going.

The train did not stop anywhere. In Ostrava we were taken over by the Gestapo and Czech gendarmes said their goodbye. They

knew where they were taking us.

The first mass transport of gypsies and gypsy half-breeds

from the Protectorate, numbering 1,038 Roma men, women and children,

mainly from South Moravia, left Brno on March 6, 1943. During the year 1943, further transports followed from various parts

of Bohemia and Moravia, which arrived in Auschwitz on March 10 (the transport sent from Prague numbered 650 people) and March

19 (1,048 people from Olomouc). In addition, transports also left from both gypsy camps

: on May 7 from Lety u Písku (863 people) and on

August 22 from Hodonín u Kunštátu (768 people). The last, smaller transports left on October 19, 1943 (from Prague and Brno, 92 people) and

on January 28, 1944 (from Prague and Brno, 37 people). In total, the Protectorate authorities gradually deported about 4,500

Roma and Sinti from the Protectorate to the gypsy camp

in Auschwitz-Birkenau. More than a hundred people were deported by

the Protectorate authorities individually.8

As part of the deportations from the Reich, almost 900 Roma and Sinti from the territories of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia

that had been affiliated to the Reich in 1939, were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau as gypsies and gypsy half-breeds

. They

were included mainly in the deportations registered on March 7, 1943, March 14, 1943, March 17, 1943 and April 9, 1943.9

In total, the Nazis deported about 5,500 Roma and Sinti from the territory of the present-day Czech Republic to the gypsy

camp

in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Most of them did not survive the camp internment.10

Next chapter: Survival in the gypsy camp