Childhood

I was born in Prague in 1929. My family was fairly well off and comfortable. We had a large five-room flat on Palackého nábřeži. My father was a corn dealer, he had a warehouse in Čáslav and he bought corn from the farmers and then sold it on the agricultural commodities market in Prague. My mother was a housewife, as was common at the time. We also had a cook, who was later to play an important role in our lives. She worked for my grandfather, then for my parents, and finally, after the war, she no longer worked but she was like a member of my family. My father came from Bučice, where his father had had a general store. After his parents died he moved to Prague. My mother came from Ledeč nad Sázavou, where her family had a mill. She came from a large family, I think she had three brothers and two sisters, who then moved to Prague sometime in the twenties. As well as a cook we also had a nanny, who took us to school, on walks and all the normal things that children require. I have very happy memories of my childhood.

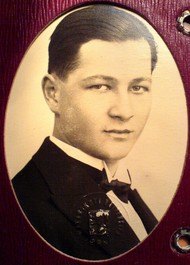

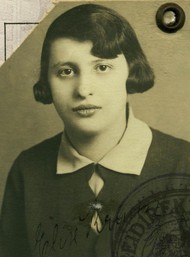

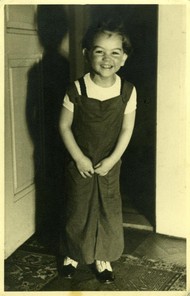

Toman Brod with his mother and elder brother before the war

Terezín

Then came July 1942 and transport AAu [27.7.1942 from Prague], which we left on to Terezín. We arrived in Bohušovice, and since the small railway to Terezín had not yet been built, we walked the last few kilometres, dragging our luggage with us. It was a fairly plodding journey, but in the end they took our luggage away from us anyway, as some sort of punishment for the assassination of Heydrich. All we were left with was our hand luggage, which was a big handicap, because we were not at all equipped for winter and for normal life in Terezín. My mother lived in the barracks, the Hamburg Barracks, I think and my brother and I lived in the Hannover Barracks to begin with, but soon afterwards we were transferred to the young people's home in L 417. This was a former school, and we lived in the gym, which at that time served as the temporary home of all the newly-arriving boys. I didn't stay long there, because I fell ill with scarlet fever and was sent to the infectious ward in the hospital. By complete chance I lay in the same bed that before me Jiří Pick, a former school friend, had lain in and died in of scarlet fever. In 1938 we had made a collection among the children for the defence of the state.

The living conditions in Terezín varied. Old and ill people fared the worst. They usually lived in houses that from the ground floor to the attic were overcrowded, dirty, full of insects, a pit of infectious diseases, without sufficient sanitation. These people also suffered the most from hunger. They were mainly German Jews, who received no food parcels from home. They died in Terezín in large numbers.

The Jewish administration did not have enough money to improve the situation for all prisoners, and so it took most care of the children and young people, since in them it saw hope for the future. This is why we, in the children's houses, lived in somewhat better conditions.

When I recovered in autumn 1942 (I also had jaundice, as a complication of scarlet fever) I returned to L 417, where I became part of the boys' team led by Ota Klein and Leoš Demner. I had several different leaders after that, but ended up mostly in class 9 with Arno Ehrlich. Each class in the school was something of a miniature home, and each was a peculiar unit of its own, since the educators brought their charges, the children, up in the spirit of their own political persuasion. Eisinger was a communist, so he educated children in socialist and communist ideas. Class 7 had a Zionist educator, who taught the children in the spirit of Zionism and taught them Hebrew songs. I had never been inclined towards Zionism, I stressed that we were Czech Jews and people who had a relationship towards Czechoslovakia and the Czech lands, and I had never imagined that after the war I would not return to Prague and live in Czechoslovakia again. So our home was the Czech boys' home, under the leadership of Arno Ehrlich, who is now called Erban and lives in Florida. This chap, not much older than twenty, educated us in the spirit of scouting. We learnt the principles of scouting morality, we played scouting games and learnt various scouting skills such as how to tie knots and so on.

We even published a magazine. You hear most about the magazine Vedem, which I think is rightly considered the best, and which was published by the boys in home number one, but in fact each home, each number, each class had its own magazine. So we founded a magazine, and because I had a reasonable - although not outstanding - amount of artistic talent, I used to make the cover for it. I remember about three issues, maybe. Each issue expressed some principle of scouting, such as helping one's neighbour or protecting the weak, or the oath of justice and loyalty. I tried to express it through the hand and its various movements. I also remember that we read a book there that I never saw again after the war. It was a book about the Boer war, about youths, the Boers, fighting the British. Every evening one of the boys would read aloud a chapter from the book. It was a lovely book about how people desire freedom and are willing to sacrifice their lives for it, they are honourable and just people and they fight against their oppressors. Those were beautiful moments, when we were carried far away from the greyness of Terezín life, back into the past, but into a past filled with heroic and famous deeds and the fight for freedom.

In addition, music played a huge role in our lives. It was not only an aesthetic education for us, but an erotic one. In the gym, which in the meantime had essentially been converted into some sort of concert or theatre hall, there were benches and a podium, and Schächter rehearsed his concert version of the Bartered Bride there. We boys used to go to his rehearsals in every free moment. It was music that penetrated our hearts and souls, and we knew every note, every recitative and every aria, and we could sing them, although somewhat artlessly. He then did the same thing with The Kiss. I still find the music of those operas extraordinarily ethical, aesthetic and beautiful, and whenever I hear them it is a wonderful experience. I remember a moment during the premiere of the Bartered Bride in the school in L 417 when the whole audience sat listening in tears, incredibly moved and incredibly uplifted. I was talking about it recently to Karel Berman, who had been one of the performers. I told him what a gift it had been to us, what a great help to our emotional life and for the aesthetics of our life in Terezín.

We ourselves tried to rehearse and perform theatre and cabaret, which was also a way of getting to meet girls. We invited girls from the neighbouring girls' house, I think it was L 410, and together we rehearsed poems, such as Wolker. It also enriched us by giving us social experience and teaching us how to be friends with girls. This was all on a completely pure level, very - gallant, if I might use that word, or knightly. None of the boys ever dared to say anything vulgar. I even remember that when I was still in class one, two doctors - one male and one female, both young - gave us a lecture on sex, and that absolutely no one took it in any sort of vulgar way. Everyone accepted it as something that was ahead of them, that was part of life and that should be talked about as befitted it, not in any sort of pejorative or vulgar way. That remained with us - and with me in particular - all my life.

Sporting events were hugely important to us. Each home had its own football team, and we organised tournaments that took place up at Šance (when it was open), where there was a football ground. We made our own charts and our own football strips. On the ground floor the women had a sort of workshop where they would alter the boys' strips and make the most necessary alterations to clothes. They made us primitive football strips, but strips nevertheless. Everyone was pleased to be part of a team that was close and had a goal and a mission. The friendship of the boys in the home was a great help. It was one of those unique things, which I remember with love and emotion. Of course, we had our squabbles from time to time - not everyone, for example, was able to put up with his nickname with good humour - but there were never any fundamental disputes. If anyone behaved badly or vulgarly, the elder of the home (each home had a boy who acted as the elder) would take a decision, and if it was a more serious disagreement, Arno would come and explain to the boys that they were not allowed to behave like that, and that if they wanted to be scouts, they had to adhere to scouting principles. There was a sort of certainty there that when the war was over, we would stay friends, that it would be a great help in our further lives, and that we would always meet as people who were adult, no longer humiliated, but still honourable and friendly. Everything turned out differently, though, and I think that most of my friends died. I have forgotten some of their names, but I can still see their faces vividly in front of me.

My mother, surprisingly, bore life in Terezín with incredibly great courage. This was despite the fact that she had never worked in her life, since it was not thought right in a well-to-do family. She was a lady, not a snobbish one, but a woman who had lived in comfort and whose main entertainment was bridge. At home she had had a cook to do the cooking and a nanny to look after the children, and she had thus been relieved of those worries. On arriving in Terezín she immediately reoriented herself and became a normal woman who had to work hard. In the square was a home for the sick, old and for mentally and physically handicapped children. She was in charge of a group of children who were physically and mentally handicapped. She was always enormously kind to them, but I was afraid of the children - to me, any abnormality seemed terrible and incredible. I vividly remember a boy who had a huge, hydrocephalous head, but I found the idea of touching his head unimaginable. My mother said to me: Come on, don't be afraid of him, he won't do anything to you, he's a lovely boy. My mother herself was tremendously courageous in bearing the hunger and misery of life in Terezín

She would make semolina and soups for us from the parcels that our former cook sent us from home, but she always cooked them for me and my brother rather than herself, although she herself was certainly hungry. Her main concern was that the children should not suffer as much as the others suffered. To tell the truth, although I saw terrible misery in Terezín, old people who stood by the food hatches begging for a bit of soup or the remains of potatoes or potato peelings, we children did not suffer from real hunger. In our school, things were set up so that the parcels that could no longer be delivered were distributed among the children, as a reward, for example.

My brother went to work, but we children only did a negligible amount of work in front of the school, where there was a small garden. We tried to grow things there, but I think we always ate them before they grew very high, so it wasn't much use. But we did go to school and to regular lessons. I can't remember the teachers now, but I remember that we were taught arithmetic, geography, history I think and other subjects. We also had visits from a rabbi who explained the essence of the Jewish holidays to us. I think it was fairly well organised - of course, it was in secret, there was always someone standing guard outside, and if a policeman or a German was coming, we had to hide our books and pretend we were playing. I think it worked quite well, and that we did not neglect this part of our life.

Toman Brod.

Terezín was a period of growing up for me, a time when the world opened up in front of me, and when we never, not even for a moment, thought that we would not survive. To us, it was always a kind of intermezzo, a bad dream. We thought that our real life still awaited us, and we never believed for a moment that we might not live to see that life, that freedom. Of course, the songs about who minds the dark shadow of the fortress, who longs for the city on the Vltava, show that we did feel terror, melancholy and homesickness, but we always managed to overcome it in some way, daily life went on and we did not lose faith. We also started to take more pride in our appearance, to make sure that - if possible - we were well-dressed, that we did not look like tramps and that we were attractive to girls. Life in Terezín was not, for me, the horror that came later. My brother by that time was no longer in 417, but in Q 317, and I remember one shocking experience when I went to visit him one day. The windows of his room looked out over the road that ran through Terezín. It was one of those autumn days, November. Suddenly a truck drove past and it was full of some sort of figures in striped clothing. This was my first encounter with real prisoners. They were said to be prisoners from the Terezín (Small) fortress. It was only a brief moment, but the horror of those people, as if from another world, took root in me and is still firmly engraved on my memory.

My brother, who was two years older than me and was sixteen, began to take an intense interest in politics. He was a communist, and he tried to initiate me into communist ideology and politics. But because I was in opposition to my brother, as tends to happen with siblings, I made light of it and said: Stop going on about it, it's your business, I have other interests. Although we were of course interested in the development of the war, and devoured all news from outside hungrily, I cannot say that I was as enthusiastic about communism at that time as my brother.

One day we were scheduled for a further transport from the east, but we were pulled out of it. I said to my mother at the time: Please, why are you taking us out, let's go somewhere else. It was mad, stupid childish naivety. Terezin is OK, but it might be better somewhere else. My mother was more sensible and, understandably, did not listen to my attempts to persuade her. I think that was what saved our life. My cousin, who had arrived with the Ak-transport [the Aufbaukommando, or construction commando] and had some degree of influence on the Jewish administration, pulled us out. The Ak were somehow privileged. The next time he was no longer able to do so, however, we were included in the December transport in 1943, and this is where the real apocalypse begins.

When we stepped on to the ramp on that freezing December day, we were given a few pieces of bread and salami to take with us, and - I think - a jug of tea. They also gave us a single bucket as a lavatory, for a whole truck of about a hundred people. Half the truck was taken up by the luggage we had taken with us, and half by people. Then they just closed the truck, no airholes in it, no windows. It was unimaginable for me that people might go somewhere in such conditions. We travelled for an incredibly long time, I don't know whether it was cold or hot, but at any rate we were enormously thirsty, and of course we had drunk everything immediately. The train kept stopping somewhere, we couldn't breathe, the whole journey seemed endless, but it might have been two days and one night. The bucket that we had been given instead of a lavatory overflowed and ran over, we were dirty, it was disgusting, a real apocalypse. There may have even been people in the truck who were already dead.

Auschwitz

Then came a terrible shock: we had arrived in Auschwitz. The doors opened and they shouted at us: Raus, raus [Out, out], and there were dogs barking. There were SS men standing around with wolfhounds, those bluthunde

, straining at us. I saw the figures that I had seen for the first time in the van, the striped men with sticks, also shouting in a foreign language - Polish. In the distance - it was a freezing night - there were regular rows of lights, and above that was some sort of dark shape - it was a balloon, I don't know whether it was an observation one or an anti-aircraft defence, but I know that it was a terrible shape, which hung there in the dark and was only lit up by flares of light. I was shocked at the brutality of our reception. They drove us with sticks into vans, and then we drove at a terrifying speed the few kilometres from Auschwitz to Birkenau. My first impression when I arrived there was that I realised what those lights were. They were lit-up wire fences, charged with electricity. Despite the speed at which we were going I also noticed that there were signs with skull and crossbones saying: Halt, stój, Hochspannung, lebensgefährlich [Halt, high voltage, danger to life] or a similar inscription. In Terezín they had always said to me: When you see the electric fences and the signs in front of them, you're in a concentration camp. We of course had no idea where we were, but at that point I realised that we were in a concentration camp. And that it was something terrible, something totally different from Terezín. Then they drove us - all the men, women and children - into unheated sheds where there were essentially just a few bare boards and no covers. My brother and I huddled together on one of the boards, and it was probably the only night when I hoped that I would never wake up. But I did wake up, and then they took us into some sort of room, close to the crematorium (which I did not know at the time), where we were forced to strip naked and they shaved us. They completely shaved our heads and tattooed a number on our left arms.

We didn't yet know that we were a mere twenty or thirty metres from the gas chamber. My one desire after that night was to drink something. We were told that we were not allowed to drink the water there, because it was typhus-ridden, and so we begged for some tea and I offered my watch to some Polish man for a cup of tea. They took my watch in any case, and then when we were given some tea, we drank the cup in one draught. The feeling of thirst was so intense that I can believe what Lanzmann describes in his film [Shoah], that people were desperately thirsty, and that for a cup of tea they were willing to strip naked and go to the gas chamber. Then they gave us some rags that we had to put on. They were prison clothes, although they weren't yet striped clothes. Then they returned us to the camp, which was actually good fortune. Of the many transports that went east from Terezín, only two in my year provided a hope of survival. Those were the transports in December 1943 and May 1944. Other than that, 99% of my year was condemned to destruction, to death.

The family camp

Life in camp B2b - the family camp - was full of horror for me at the start. Even then, I said to myself that the difference between Protectorate Prague and Terezín was about as deep and intensive as the difference between the Terezín ghetto and life in this concentration camp. And this was in spite of the fact that the family camp was privileged in its way. But the cold and the shock before you got used to it was terrible. That is, if you can get used to it, if the horror is not absolute, if there are some conditions for life, then you get used to it, and then it does not seem so bad, then you start to look on the brighter side of life. Just as in Terezín we made use of every opportunity to make our life bearable, so in B2b in Birkenau the people around us tried to make life a little easier - especially for us, the children.

We lived in an ordinary block, but during the day we went to the children's block. This had been set up as the result of the influence of Fredy Hirsch. He was an incredibly charismatic figure, a German Jew originally from Aachen, well-built, a sportsman, a good-looking man who did everything he could for the children. I don't know how he got the privilege, but the fact is that the children's block existed, and that we were able to spend the day in relative warmth. The hunger was terrible. For me, for a growing boy, the soup and bread that we got was enough to start with, but after a few days I was tortured by hunger. In the morning there was nothing to eat, and we got through the whole morning on just coffee - or rather a little warm, black water. The first real food came at lunchtime in the form of that bowl of soup. The mornings stretched out endlessly, but we nevertheless found ways to entertain ourselves. We had educators there, and they told us many things, although I don't think they could be called actual lessons. A former sports editor who in 1936 had watched the Olympic Games in Berlin told us, very vividly, how the black athlete Owens had won the long jump and the hundred metres, and what a terrible shock it was for Hitler, who had thought that Germans would win. Hitler refused to shake hands with Owens. We loved that story, because all boys loved and love sport. And, moreover, we too wanted to be victorious over Hitler some day. We also had some sort of cultural life, we even tried to perform theatre, we rehearsed various pantomimes and poems. I still remember how we learnt Nezval's Edison as a choral poem.

In the middle of the camp was a horrible muddy area. If it was not freezing, we had to wade, our feet in clogs, through this completely bottomless mud. The water, understandably icy, only worked sporadically, and the only place to wash was under a tap in the washrooms. The latrines were common - one row for men, another for women.

Meanwhile, we had already heard rumours regarding the purpose of the gloomy buildings that stood a few dozen or hundred metres from our camp, with a high chimney, continuously spewing out fire and smoke. The view was a chilling one, especially at night, when the flames from the chimneys leapt up several dozen metres into the air. They were crematoria, where people were burned. I don't know if at that time we had heard anything about the gas chambers, but either way, it was a terrible thing to imagine. Nevertheless, I did not think then at all about the fact that we might end up like that. For me, the most horrifying fact was the coarseness, brutality and callousness that I came across directly. It was not only personified in the ferociousness of the camp's Lagerführer Buntrock - that was a nomen omen, we called him Bulldog. He was a criminal and utterly brutal murderer. At his right hand he had another murderer, the prison Lagerälteste Arno Böhm, who was never seen other than with a stick in his hand, running about the camp, roaring and beating people. I, however, was pretty shocked to find that not only Germans, but our own people, who had come to Auschwitz three months before us, behaved so coarsely, roughly and brutally. This was something I think the Germans really succeeded in - that some of the prisoners adapted very rapidly to the conditions. All it took was a few weeks or months for relatively decent people, who had gained power over their fellow prisoners, and were themselves also subjected to cruel conditions and violence, to transmit the violence on to other people. For me it was incomprehensible to see them slapping a defenceless person, who could not defend himself, beating him with a stick - maybe just for some totally insignificant misdemeanour. I found the brutality of life there quite horrifying, and so the chance to live in relative seclusion from this horrible world, in the children's home, was in its way a liberation for us, especially in those first weeks and months.

Mengele also used to visit the children's block, and I remember him very well. However, Mengele was not an ogre, he was not a murderer of the Buntrock type, he was a very refined and decent person, who may have worn an SS uniform, but in white gloves. And he was always very kind to the children and asked them if they were happy with their educators and if they needed anything. He behaved more like an uncle, like a good guardian of the order and welfare of the children. At that time we already knew that he was particularly interested in twins, which he took somewhere, but what he did with them, I don't know. At least in my eyes, Mengele at that time did not represent the terrible murderer that he in fact was. That role was filled by other people.

Among the SS men, most of whom behaved roughly, there were also relatively decent people. They included a Romanian German, Viktor [Pestek]. He was a smallish, black-haired man with rosy cheeks, who could not have been much older than twenty. He did not behave badly to the prisoners, and he tried to fulfil his tasks in such a way as not to harm anyone. I will not describe his famous escape, since although I was there at the time, I do not have any details.

In March 1944 came the liquidation of the September transport. Half of the family camp was suddenly emptied. They took them to the quarantine camp next door, and in our camp left only a few sick people in the Krankenstube in the sick block. They wanted to pretend that the sick people couldn't go with the others because it was a labour transport. There was talk that they were going to a place called Heidelbreck. However, shortly after the transport disappeared, rumours began to spread that Fredy Hirsch had committed suicide, and that they had not gone to Heidelbreck but to the gas chambers. On the other hand, we were confused by reports from the May transport that came to our camp and told us that letters had come to Terezín from this so-called Heidelbreck transport, dated a few weeks later. It was, of course, fraud, but in its way it comforted us, because people always prefer to believe positive stories and to push horror and death away.

Then things in the camp suddenly started to get better. I don't know why. The members of the new transport were not any better on average than the September people, but I know that they no longer succumbed to the brutality and callous, rough and cynical morals to which some of the people from the September transport had succumbed. It might have only been my imagination, but suddenly I felt some sort of change, that things in the camp were freer and more democratic. Apart from Ada Fischer, of course. Ada Fischer was an executioner who had taken on the execution of those few boys in 1942 in Terezín. In Birkenau he took on the role of kapo. What a creature he was, crippled both physically - he was hunchbacked, a kind of goblin - and mentally. He was utterly brutal and would beat people with a cane with absolutely no hesitation. I heard that later, when he lost his position and power during the liquidation of the family camp, that the prisoners themselves beat him to death in one of the trucks that left Auschwitz. If that is true, then it was utterly deserved

After the escape of Lederer and Pestek, criminal roll-calls were announced. At four in the morning we had to line up in front of the blocks and they counted us. There were also afternoon roll-calls. It was, of course, meant to punish us, but by that time it was spring, and I remember that when we had been standing there for hours on end, it began to grow light, and a spring wind began to blow, and suddenly you felt you had some sort of strength again. The horror of the initial shock had already passed, and we were beginning to organise ourselves in the camp in a certain way, to grow closer to each other. Life had stopped being so terribly unbearable. And again I'd say that the dawn and the coming spring brought one of those sudden moments of joie de vivre. It wasn't particularly beautiful in those Polish marshlands, but it was spring, and that brought new hope.

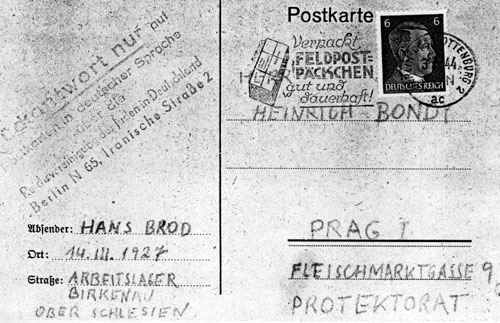

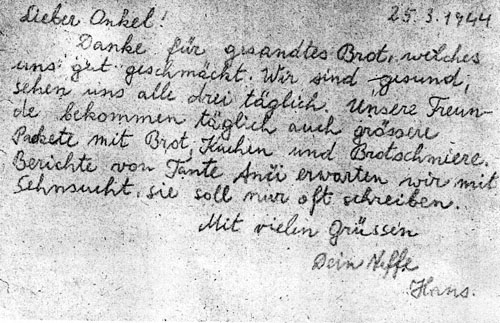

I should also mention that among the privileges of the family camp was that we were able to receive parcels. As a child, I was not allowed to write to anyone, but my brother and mother wrote letters to our friends in Prague from the Arbeitslager Birkenau bei Neu Berun, in which they indicated in some sort of allegory that it was possible to send bread and some sort of spread. The letters got to Prague, and our housekeeper really did do everything she could and sent us two or three parcels to Birkenau. It was a huge help to us, because we were still terribly hungry - the hunger was never-ending.

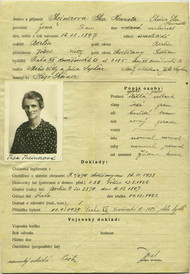

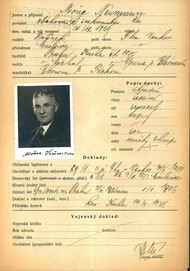

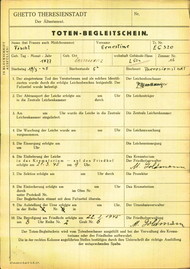

A postcard sent by Toman's brother from Auschwitz.

When spring came, our thoughts turned a little to other things. It sounds awful to talk about love blooming in a concentration camp, but it did. I remember two Hanas, I don't know if they're still alive, but I don't want to see them today, I want to preserve them forever in my memory as charming young girls. They were my first loves, and will always stay in my memory as young fourteen-year-old or fifteen-year-old girls.

Fredy Hirsch was no longer alive, but other leaders continued in the same spirit. I know that some painters even decorated the walls of the block with fantastical paintings of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and other fairytale creatures. We also acted theatre plays. One SS man even came to watch our performance.

Then came June 1944, and with that, our time was to be up. Once again, rumours began to spread that the camp was about to be liquidated, that there were hard times ahead of us and that something terrible was about to take place. The whole existence of the family camp is a mystery to me. I reject the explanation that it was meant to be a show camp for a visit by a foreign delegation. I believe it was completely out of the question that the Germans could have brought a foreign delegation to the family camp in Birkenau, a few dozen metres from the gas chambers and crematoria. It seems more likely that they wanted to calm the Terezín prisoners by showing them that we were able to write letters to Terezín.

When the camp was being liquidated, the Germans organised several selections. First Mengele sent the men away, then the women and finally the only people left in the camp were the old people and the mothers of children. I stayed there with my mother, my brother left, and after that I never saw him again. At the last moment someone persuaded Mengele to make a last attempt, a last selection of about a hundred boys aged between about 14 and 16. I remember as if it were today how I stood in the children's block with the Lagerschreiber

[camp clerk] and others. Mengele stood in the middle, and those of us who were the right age walked up to him. In one hand we held our boots, in the other our clothes, and we filed past him, naked. In fact, Mengele saved my life, because he judged me capable of further transport. Several dozen boys shared my fate. I was relatively tall then, but I wasn't yet thin and physically-ruined, so I still made a good impression overall.

The men's camp

I was sent with the other boys to the Männerlager

[men's camp], specifically to a block where there was a Strafkommando [criminal commando]. These were prisoners who had committed some sort of offence, and who as punishment were subjected to even harsher discipline and harder work. The block was headed by a Polish prisoner called Bednarek. To start with, he considered the fact that boys had come to his block to be a huge distinction, and boasted about us, led us when we had to assemble, even organised us into some sort of football team and set up a ping-pong table for us in the yard. But his initial pride in the fact that he had boys there soon evaporated, and after that he forgot about us. We lived a normal camp life, without any sort of privileges. On the contrary, we witnessed terrible scenes that took place in the yard of the Strafkommando. They would bring in a prisoner who had either tried to escape, or had committed some other offence, and would beat him horribly. Although they drove us inside, we could see through holes in the wall what the SS men were doing to them in the yard. They beat them in terrible ways, they were shocking scenes. Next to us was the block where the Sonderkommando lived [the special commando that serviced the gas chambers and crematorium]. We boys were not subject to the Strafkommando regime, and we could go outside and visit prisoners from the Sonderkommando. It was from them that we found out what had happened to the rest of our transport. That was when I found out that my mother had died in the gas chamber only a few dozen metres from me, together with the other prisoners who had not been chosen for any kind of work. I had had no news of my brother, but shortly afterwards a prisoner from the quarantine camp brought me the news that he was alive. The man was even willing to take a bit of bread to him. But that was my last contact with my mother. I also remember that someone smuggled a letter to me from my mother, saying goodbye and hoping that we would see each other again. I don't know if she knew that she was going to her death, but it was more the sort of letter that you might write if you were going on a journey.

All this was very cruel news for me at that moment, but we had already seen so much death and destruction around us that it almost had no effect on us. It was at that time that I experienced probably the most dreadful scene of my life. Only now do I realise just how appalling and chilling it was. In summer 1944, when the Hungarian transports had begun to arrive, Auschwitz was a huge death factory and the crematoria were working all day and night. We had a certain privilege in that we were able to go outside the men's camp (not outside the Auschwitz camp, of course) in order to get firewood, with carts that we pushed ourselves. One day we were going past the unloading ramp, which for us always meant a huge chance that at some unguarded moment we might pick up a rucksack, shirt, boots or a loaf of bread that had fallen to the ground, and push it under the wood. Everything was considered hugely valuable. One day, when I was in the Sonderkommando block, a prisoner showed me a box full of gold teeth. But gold meant nothing to me, gold had no value to me at the time, what was valuable to me was bread, or soup or a shirt. One day, as we were going past the crematorium, some women and children were walking from the ramp to the crematorium. They were walking at a leisurely pace, some of the women were carrying children, some were holding them by the hand, as if they were just going on a walk, going on a trip. An elderly SS man was accompanying them, and everything was quite calm. I was standing next to the kapo, who was a Reich German, and I saw that tears were running down his cheeks, and heard him whispering to himself: Solche schöne Frauen, solche schöne Kinder. [Such beautiful women, such beautiful children.] At the time I thought that it was just the practice, that that was the way it had to be. Our emotions really had been drained dry by that time. The scene still wakes me up in my dreams, but at the time it did not provoke the same horror in me.

Next door to us was the gypsy camp, and we used to talk to the gypsy girls through the barbed wire. Some of them were Czech, and we were glad to be able to meet with people from our own country. Then one day the gypsy camp disappeared. We knew they had gone to the gas chambers.

Instead of the gypsy camp, some prisoners from Lodz arrived in summer 1944. My uncle's family had been in Lodz since 1941. When I discovered that there were Czech Jews there, I called for my uncle and cousin, who was still a boy, through the barbed wire. I even managed to give them some cigarettes and food. Above all, I was glad that they were alive. Then, by some remarkable coincidence I caught a glimpse of my aunt and her daughter in a transport from the women's camp, and I was able to call to them: Uncle and Márius are alive. And they still remember it, because for them it was the only news they had had that their dear ones were alive. My uncle, the strongest of them all, a sportsman, didn't survive, but all the others did. It was a miracle that out of a four-member family, three survived.

Then came autumn 1944 and there started to be rumours that the Red Army was drawing near, and that the camp would be liquidated. We experienced the Sonderkommando uprising in September 1944, and we saw how the flames and smoke leapt up from the crematoria. SS men stood on the roofs and watched the event with telescopes.

We also experienced prisoners escaping and being caught. It was always a terrible scene: they brought them in, the camp band had to play, they put a sign in their hands saying Hura, wir sind schon wieder da [Hurray, we're back again] and to the accompaniment of the band they put them on a sort of wagon and drove them, mockingly, to our block, the Strafkommando, where they gave them a terrible beating and after a few days executed them. Luckily they didn't take us boys to see the execution.

One day in October 1944, as I was peeling potatoes with a few boys in the kitchen, they suddenly made a selection, and some SS man, not Mengele this time, pointed right, left. But since he sent most of the boys to the right and me to the left, I ran over behind his back to the group on the right. I think that deceit saved my life.

Gross-Rosen

They took us to Gross-Rosen. The journey was not as terrible this time, because it did not last as long and it also did not take place in the winter, but on a lovely autumn day. Gross-Rosen is in Klodzko, not far from Broumov, and the fact that we were only a few kilometres from our own country gave us huge hope. However, we still had to live through the terrible winter of 1944/45. For us, the conditions were worse than at Birkenau. It is paradoxical, but each prisoner finds that, when he gets used to a certain camp, he gains certain contacts, experiences and the ability to organise

things, in other words, to procure the things necessary for life. When they take him out of that environment, he is completely uprooted again, he finds himself in completely new conditions and the prisoners who were in the camp before him have an advantage.

This was our situation now. The conditions there were worse, the living quarters were worse, there was even less food, and above all winter was starting. And we weren't dressed for it at all, we had only thin clothes, no coats and practically no underwear. The hunger there was terrible - no food parcels could reach us there, understandably - and no sort of organising

was possible. We had no privileges there, we were normal men put to work.

That work was one of my most terrible experiences. We went to the sawmill to load and unload wood in and out of wagons, or we went to cut down trees and bring wood back from the forest. It was in the mountains, in the snow, in the freezing weather, with insufficient clothing, and on top of that the hunger and heavy labour.

Added to that there was another horror that there hadn't been in Birkenau, where strict attention was paid to hygiene - lice. I saw truly apocalyptic scenes in which they moved in layers over people who couldn't protect themselves and who really were being devoured by lice.

My worst experience of the work there was when one day they took us to some fat cables covered in tar, and gave each of us one section, about five metres long maybe, which we had to carry on our shoulders - this was a cable about 300 or 400 metres long - up a hill. At first it was manageable, at first you said to yourself, well, this isn't so very heavy. But the journey lasted too long, it was uphill and we walked slowly, because understandably people were tottering, so that the cable got heavier with every step, and cut into our shoulders. That was when I understood what the Calvary probably was for Christ, when he was carrying his cross on his shoulders. Because we really were carrying the cross, in the metaphorical sense, up to the top, and it was never-ending. We did that twice a day, once in the morning and again in the afternoon.

It was not just the heavy labour but the overall conditions that were inhuman and terrible. We essentially slept just on straw, with a light covering, and in the morning we had to get up at five o'clock in the freezing dark. We had a little hot water that was called coffee, and then we walked several kilometres to work. But I was able to walk, and so walking was good work for me. The further away our workplace, the better it was, because we finished work earlier. There were also Ukrainians there who had been taken by the Germans to do forced labour in the Reich. Some of them behaved well to us and would give us a bit of food, for example, that they hadn't eaten themselves. But essentially there was hunger, cold and work from morning to evening outside in the inhospitable wood, where we considered it a miracle if we could make a fire and sit down for five minutes and warm ourselves. It was impossible there to get hold of any clothing.

It was hardly surprising that we soon became Muselmanns. A Muselmann was a person so thin and weak that he could hardly stand up, and was condemned to death. By January 1945 I could no longer go to work, and in some way I managed to get to the Krankenstube in the camp block, which had the single advantage that you were in the warm there. There was just as little food there as outside, but the fact that you were under a roof was a huge advantage and chance. On the other hand, the fact that you were just lying there all day meant that you spent all day thinking about food. And then a miracle happened to me. My hunger had reached such a peak that I - probably quite delirious by then - naively decided that I would pray to God to give me some food. Believe it or not, at that moment a medic came and gave me some soup. All the other prisoners lying next to me started to protest: Why are you bringing him soup? And he - I can still remember it today - said: He's still a child. Since I'd been there about a week or fourteen days by then, someone suddenly decided that they'd transfer me to another camp. That ended all my contact with the boys, with my colleagues, with whom we sometimes, at a moment when we had a break from work, used to reminisce about our childhood. We used to say to each other that today, sixteen-year-old boys in Prague or elsewhere in the civilised world are going to dancing lessons and living normal lives, while we wretches are here, dying of hunger and cold. And thus we mused on our fates. When they took me to another camp, my contact with my friends from Terezín and the Birkenau Männlager ended, and I never found out whether any of them survived.

It may have saved my life again. In a prisoner's life there were so many chances which you did not know whether to take, so many twists of life over which you had no influence. I was taken to a camp several kilometres away. [According to the data of the museum in Gross-Rosen, T.B. was in Märzbachtal (Riese) from 25 January 1945.] It was an old factory, with a yard surrounded by a wall, and that was the whole concentration camp. There was no going to work there, in fact I don't think there were any labour duties there, it was more of a camp for dying. It was there that I saw the terrible scenes of people who could no longer move and were being eaten by lice. The lice were indestructible, and if you spent an hour picking them out of your shirt, in another hour the shirt was full of them again. Moreover, it was so dirty there that I got a sort of festering boil, which the local medic just sliced off without any sort of disinfection - I still have the scar from it. He bound the wound, but the lice got into it, under the bandage. That was the apocalypse, those lice, the apocalypse. Not only are they dangerous but you continually have the feeling that something is eating you, that something is bothering you, that you're itching, you have to scratch yourself, you feel unclean.

The lifesaver was to have a bowl. Anyone who didn't have a bowl didn't get any food. One day someone stole my bowl. They also stole my bread, of course, when I had hidden it - for better times - under my pillow. Of course that happened, because hunger makes people into wolves, and I might have stolen bread too, if I could have got close to any. But the worst thing was that I suddenly found myself without a bowl, and so I couldn't get any soup, which was an incredibly important part of our diet, because it was our only hot food. Now, for a change, it was me who wanted to steal a bowl, but everyone looked after their bowl, and the only bowls that the prisoners had were those that they peed into when they didn't want to go to the toilet in the night. In the end I had no choice but to steal one of those bowls. I should hope I washed it out, but it was probably fateful to me, because I then got typhus. At that point, however, I saved my life with it, because at least I could get soup.

By that time - spring 1945 - all my strength was ebbing away, and I began to succumb to a sort of dreamy mood, I was overcome by hallucinations. We no longer had to go outside, and so I spent all day lying down. And anyone who started to lie down, started to die. It was the start of the pre-death agony, when I was overcome by a sort of sweet inertia and tiredness. But suddenly, there appeared in my mind - as when you view a film from the past - a picture of Prague and the whole of my life, my childhood and the people whom I had loved. And so I said to myself: The end of the war must be getting close. If I've lasted these three years, then I have to last the next few weeks. I'm not going to die here amid this filth, dirt and lice like a nameless victim. So, with the last of my strength, I got up, and - although I could hardly stand, I was so weak - some sort of determination won inside me. I declared myself able to work again. I don't think we got much work done, but the fact that I picked myself up from that lethargy, from that horizontal position, into some sort of vertical position, however tottering, may have saved my life.

Liberation

We were unlucky in that we were in the Klodzko pocket, where there was no fighting and which was not liberated until later. It was not until May 8th in the evening that the news got round that the SS had left and that the camp was free. We immediately went out, and I know that I spent the night of May 8th in some stable, where a horse licked me. In the morning I got up and started to walk, or rather hobble, without even knowing where I was going. I just wanted to get away from the camp and to get home somehow. I found a jar in a ditch with the remains of some jam, and so I began to lick it. At that point a Russian soldier went past. He was a typical Ivan with a moustache, in military terms an older man, definitely between 40 and 50. He took me by the hand and said something in Russian to me - something to the effect that I shouldn't be looking for food there. The Russian soldier took me to a nearby farm, where the whole family came out into the yard. They were more like city people who had a farm. The Russian soldier indicated that he wanted two or three eggs and a hen for himself, and that they had to look after me. They immediately did what he said, with great decency and willingness, and took me in. As far as I can remember today, it was a very comfortably-furnished building, with a bathroom, well-equipped. Without any inhibitions, I let the women undress me and put me in the bath. They started to call the other neighbours to look at the state I was in. I must have weighed about 40 kilogrammes by then, I was all skin and bone. It was a terrible, unhealthy-looking kind of skin as well. I was starting with both typhoid fever and typhus, and so I must have looked a terrible sight. The Germans put me to bed, gave me some nightwear and made me some strong chicken soup. I was maybe already starting with typhus, but I immediately had diarrhoea. They tried to communicate with me to the effect that if a Russian came and started to bother their daughters, I should tell him that they were treating me well. I don't think any Russians came to bother their daughters, but nevertheless, after about a week, in which my state got worse rather than better, they put me on some sort of vehicle and took me to hospital. There I was declared to have both typhoid fever and typhus, and I think they had me written off. There were German nurses there, and Polish or Russian doctors. I remember that one Russian doctor came and, pointing to me, said to the Germans who were on duty: Look, see what you've done to this man, can you call this a human hand? Is this the hand of a living person? I don't know by what miracle I survived. But I did.

After about five weeks, when I had started to regain just a little strength, they issued me with confirmation that I had neither lice or typhus and that I was capable of being transported. I wanted to go away, I wanted to go home. I had had no news of my family yet. I knew that my mother was dead, but I knew nothing about my brother. Moreover, at home our cook was waiting for me, who had in fact saved my life and was my second mother. And so I set out for home.

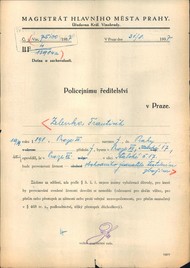

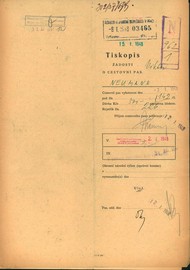

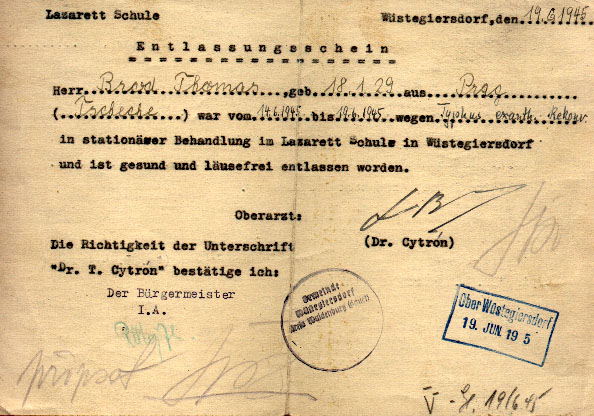

The certificate that Toman Brod received on being released from hospital

I went part of the way on foot, and part on a coal truck, then on foot again, because the train had stopped at a collapsed bridge and so I had to walk. Finally I managed to hobble into Mezilesí, which was in Czechoslovakia. I saw the Czechoslovak flag for the first time. That was a hugely moving experience for me. It was June, and everything was already functioning normally there. I got on to the express train to Prague, and got off at Denis station - with a certain amount of apprehension, because I had heard that there had been fighting in Prague, that it had been bombed and that the fighting had been around the Old Town Square. I staggered from Denis station to the house in Masná street, from which we had left on the transport three years ago. From far off I could see that our house was standing, and I breathed a sigh of relief. Then I met our housekeeper again. It was a tearful meeting.

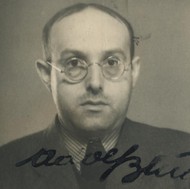

The Brod family's housekeeper

After that I had tuberculosis. When the doctor saw me, a few weeks or months later, he said: You know, I didn't dare to think you'd survive after all that, you've escaped from the gravedigger's shovel. I had an immense appetite. I lay in the sanatorium in Podolí, and my whole day consisted in looking forward to food, so I put on a huge amount of weight, and that probably saved me.