On the night of 9 November 1938, an anti-Jewish pogrom broke out all over Germany. It came to be known by the somewhat misleading and euphemistic name of Kristallnacht. The pogrom symbolised and stepped up the pace of the Nazis' anti-Jewish policies of 1938.

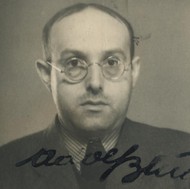

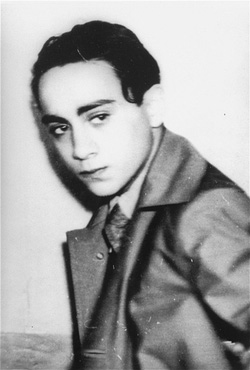

The pretext for unleashing the violence was the assassination of Ernst vom Rath, a legation secretary at the German Embassy in Paris. On 7 November 1938 vom Rath was seriously wounded by two shots fired by Herschel Grünspan, a 17-year-old Jew. Grünspan's family had fallen victim to the expulsion of Polish Jews from Germany to Poland by German authorities at the end of October. His parents and sister were among the thousands of unhappy Jews who had to spend long weeks on the border in squalid conditions, with neither side willing to accept them. Herschel Grünspan's action appears to have been motivated by an attempt to take revenge for what was happening to his parents, and to draw attention to it. He was immediately arrested by French authorities and later handed over to Germany, where his traces were ultimately lost.

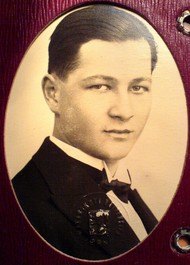

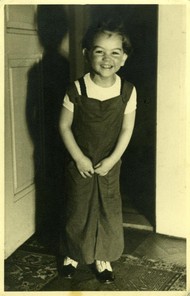

Photo of Herschel Grünspan taken immediately after his arrest, 7 November 1938. (Foto: Morris Rosen, courtesy of USHMM Photo Achives)

However, this unhappy, rash act by a Jewish youth was not the real reason the pogrom erupted. The Nazis merely used it as a pretext to step up anti-Jewish measures. Nazi propaganda painted the assassination as part of a Jewish conspiracy against the German nation, and as an attempt by Jews to stir up enmity between European states. All the German newspapers published hate-filled anti-Jewish tirades on their front pages the following day.

In Paris, meanwhile, vom Rath was fighting for his life, and on the afternoon of 9 November 1938 he died. By complete chance, on the same day in Munich the annual meeting of the Nazi old fighters

with Hitler was taking place - a commemoration of the unsuccessful Nazi putsch of 1923 in Munich. When Hitler left, at around 10 o'clock in the evening, Goebbels appeared (undoubtedly after agreement with Hitler) with the news of the death of vom Rath. He made an incendiary anti-Jewish speech calling for revenge, which the functionaries of the SA and other Nazi institutions present interpreted as a command to start an anti-Jewish pogrom. That very night, SA units in particular started to provoke anti-Jewish unrest, and to themselves attack Jewish buildings.

Selected places in which synagogues were burnt down during Kristallnacht

.

During the pogrom, which took place from the late hours of November 9th, throughout the 10th and, in some places, was still taking place on the 11th, most of Germany's synagogues and Jewish prayer rooms, considered a symbol of the presence and success of the Jewish minority in Germany, were burnt down. Jewish shops and businesses were looted and their equipment destroyed. Almost 7,500 Jewish shops were reported as having been demolished. Almost 100 Jews were killed during the pogrom itself, and around 30,000 - most of them the more wealthy Jews - sent to concentration camps in Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. They were only released if they undertook to emigrate and to hand over their property to the Reich.

The Nazi leadership cynically claimed that the pogrom was not organised in any way, and that the Jews themselves had provoked the righteous anger of the people. The Nazis used this an excuse for further anti-Jewish measures. Jews were ordered to remove the damage caused and to return the streets to their original appearance - but they were also banned from receiving any insurance payments. Moreover, at a meeting chaired by Hermann Göring on 12 November, German Jews were also ordered to pay a fine amounting to a billion marks. Kristallnacht was thus used to speed up the forced Aryanisation of Jewish property. The November pogrom of 1938 may thus be considered a symbolic and practical milestone in the Nazis' anti-Jewish policy: it marked the transition to the complete expulsion of Jews from society and, prospectively, to their physical liquidation.

-

Literature:

-

Pätzold, Kurt a Runge, Irene. Pogromnacht 1938. Berlin: Dietz, 1988. 260 s.

-

Pehle, Walter H. Der Judenpogrom 1938. Von der Reichskristallnacht zum Völkermord. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1988. 246 s.

-

Fisher, David a Read, Anthony. Kristallnacht. Unleashing the Holocaust. London: Papermac, 1991. 306 s.

-

Kárný, Miroslav. Pogrom zvaný křišťálová noc (The pogrom known as Kristallnacht). Roš chodeš. 1998. Text of article; in Czech.

-

Hahn, Karl J. Kristallnacht in Karlsbad. Křišťálová noc v Karlových Varech. Praha: Vitalis, 1998. 108 s.

-

Vojtíšková, Marie. Židé v České Lípě (Jews in Česká Lípa). Libice and Cidlinou: VEGA-L, 1999. 123 s.

-

Viz též:

-

Kristallnacht

in the border area - the 70th anniversary of an almost-forgotten event. -

Kristallnacht - documents. (In Czech)

-

Links:

-

Kristallnacht. On-line presentation on the website of the Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem.

-

Kristallnacht. Map on the website A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust showing the places where synagogues were burnt down during Kristallnacht. . (The map is not totally complete - some places in the Sudetenland are missing, for example). On the same site is amap showing the main places where anti-Jewish violence occurred during Kristallnacht.