Key and copyright. (In Czech)

The extermination camp of Sobibor was built at the beginning of March 1942, close to the village and railway station of the same name in the eastern part of the Lublin region. Together with the extermination camps at Treblinka and Bełżec, it was part of Operation Reinhard. Under the leadership of Obersturmführer Richard Thomalla, it was built by local people and several dozen Jews from nearby ghettos. In April 1942, Franz Stangl was appointed commander and given the task of completing the camp based on the model of Bełżec.

The camp was not large in area - 400 by 600 metres. The space was divided into three areas. There was the administrative part (Camp I),a railway platform with space for twenty railway trucks, and accommodation for Germans and Ukrainians. The reception

part (Camp II) was where the deportees had to strip off, have their hair cut and give up any valuables. In the third, extermination part (Camp III) were the gas chambers, mass graves and accommodation for Jewish prisoners.

Postcard written by Slovak prisoner Alice Elbertová from Sobibor on the 18th of June 1942. (Photo: Denise Elbert Kopecky, courtesy of USHMM.)

The camp staff consisted of some 20 to 30 Germans and 90 to 120 Ukrainians who had trained in the Trawniki camp. About a thousand prisoners were selected from the transports and forced to do various kinds of work in the camp. Some of them worked in the workshops or acted as servants for the higher-ranking staff, while others were used to clean the wagons and to strip new arrivals. Around 200 to 300 prisoners were employed in removing the dead from the chambers and burying them. There was also a special team of teeth-pullers

, who pulled gold teeth from the mouths of dead victims. Selection took place almost daily among the working groups, and the weak or sick were sent to the gas chambers. They were replaced by healthy and strong people from a new transport

After a transport arrived at the camp, the deportees were told that they had come to a transit camp in which they had to undergo a disinfection procedure before being taken to the labour camp. They had to take off all their things, and were driven naked into the alleged showers

. For the sick and those incapable of walking independently, the railway was extended right up to the gas chambers. The train also brought the bodies of those who had died during the transport, so that they could be buried on the spot. In the winter months the trains often brought frozen prisoners.

The gas chambers were each around 16 square metres in size, with a capacity of about 160 to 180 people. They were entered from the area in front of the building, but each also had an exit, from which the dead bodies were taken. Once the camp and the gas chambers were completed, they were tested using 250 Jews - mostly women - brought from the nearby camp at Krychów.

After three months, at the end of July 1942, it was found that the capacity of the gas chambers - about 600 people at once - was not enough, and that further premises had to be built. The camp's activity was suspended until September 1942, while three new gas chambers were built alongside the existing three. The capacity was thus increased so that 1 200 people could be put to death at the same time.

In August the camp's commander, Franz Stangl, was transferred to Treblinka. He was replaced by SS-Obersturmführer Franz Reichsleitner, his colleague from the euthanasia (link in Czech) extermination programme..

When Heinrich Himmler visited the camp on the 12th of February 1943, he saw with his own eyes the whole process of the murder of a transport of girls from the labour camp at Majdanek.

At the start of July Himmler decided to change Sobibor from an extermination camp to a concentration camp, with a munitions factory. Some prisoners were shot, while the news of the camp's closure motivated others to escape.

The station at Sobibor, 2002. (Photo: M. Stránský)

In mid-August 1943 an underground organisation was formed, led by the head of the Judenrat in the Galician town of Zolkiew, Leon Feldhendler. The group, whose members were mostly the heads of the labour workshops, planned to organise a mass escape from the camp. Later, a Russian Jew, Officer Alexandr Pechersky, was chosen as commander. Several plans were drawn up. The aim of the one that was finally decided on was to kill the German staff, seize weapons and escape from the camp (there are, however, several versions of the course of the uprising). The rebels were joined by two Ukrainian kapos. The uprising broke out on the 14th of October 1943 at four o' clock in the afternoon, and in its course 12 Germans, including camp commander Franz Reichsleitner, and several Ukrainians were killed. Three hundred prisoners escaped, but most were killed while escaping or did not survive the mine field. Those who did not or could not join the escape attempt were also killed. Many escapees were later hunted down and shot by Ukrainian guards sent on search parties. Around 50 prisoners survived the war, many of whom joined the Russian partisans operating in the area.

Watchtower at Sobibor, the only part of the extermination camp that remains, 2002. (Photo: M. Stránský)

After the uprising, the Germans decided to close the camp and to put a farm on the land it had covered, as they did at Treblinka and Bełżec. In summer 1944, the camp was liberated by the Red Army and divisions of the Polish People's Army.

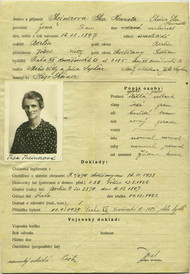

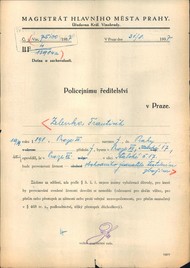

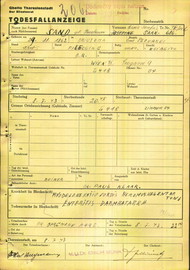

Jews were deported to Sobibor not just from the Generalgouvernement, but also from Slovakia, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Germany, the Netherlands and France. The last transports to Sobibor came from the ghettos in Vilnius, Minsk and Lida. In total, about 250 000 people were murdered at Sobibor.

After the war, charges were brought against eleven of the SS officers who worked at the camp, and between the 6th of September 1965 and the 20th of December 1966, they went on trial at the Hague. Franz Stangl was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1970 by the court in Düsseldorf.

Memorial at Sobibor, 2002. (Photo: M. Stránský)

There is now a small museum and memorial on the site of the camp.

-

Literature:

-

Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987. 437 s.

-

Kraus, Ota a Kulka, Erich. Noc a mlha (Nacht und Nebel). Praha: Naše vojsko, 1966. 431 s.

-

Mildt, Dick de. In the Name of the People: Perpetrators of Genocide in the Reflection of Their Post-War Prosecution in West Germany: The "Euthanasia" and "Aktion Reinhard" Trial Cases (Im Namen des Volkes: Die Übeltäter des Genozids in Anbetracht ihrer Nachkriegsverfolgu. Hague, London, Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1996. 442 s.

-

Gutman, Yisrael a Saf, Avital. The Nazi Concentration Camps: Structure and Aims: The Image of the Prisoner: The Jews in the Camps (Die nazistischen Konzentrationslager: Aufbau und Ziele: Das Bild eines Häftlings: Die Juden in den Lagern). Kernermann Publishing, 1997. 746 s.

-

Formánek, Jaroslav. Co zabil Jehuda Lerner (Was Jehuda Lerner umbrachte). Respekt, 2001.